Elle and I binged 1883 this month, which is why I’m falling slightly behind my reading goal. Luckily I’m still within striking distance of 100 books and I think I’ll be able to pull it off…

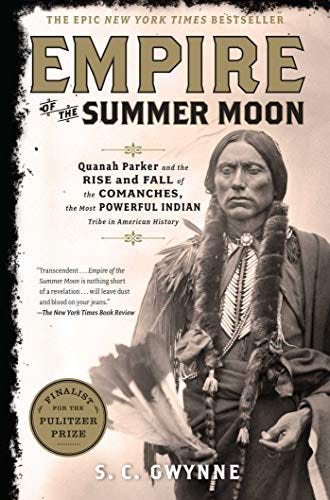

The series got us both interested in learning about the Comanches, the most formidable American Indians in the West. It seemed like Gwynne’s book was the best option to learn more. The New York Times Book Review called Empire of the Summer Moon “nothing short of a revelation” and said it “will leave dust and blood on your jeans.”

The book didn’t disappoint. Despite being a meticulous historian, Gwynne is also a marvelous storyteller. Like other great histories, Empire of the Summer Moon transports readers to Comanche land, detailing the Comanche’s brilliance without overlooking their violence.

Favorite Passages:

One thinks of Cynthia Ann on the immensity of the plains, a small figure in buckskin bending to her chores by a diamond-clear stream. It is late autumn, the end of warring and buffalo hunting. Above her looms a single cottonwood tree, gone bright yellow in the season, its leaves and branches framing a deep blue sky. Maybe she lifts her head to see the children and dogs playing in the prairie grass and, beyond them, the coils of smoke rising into the gathering twilight from a hundred lodge fires. And maybe she thinks, just for a moment, that all is right in the world.

The result of such efforts was to convince most Comanches that they were better off outside the reservation. On June 30, 1869, it was estimated that there were 916 Comanches on the reservation, but none of them were self-supporting farmers. All were living in tipis and subsisting on a combination of their own hunting, the undependable government food and annuities, and raids on Texas and on other tribal reserves. Many drifted off the government land to join the hostile bands in the Llano Estacado. There developed a pattern. In winter, more Comanches would arrive to camp on the reservation and to claim beeves and other food and annuity goods. In the spring they would drift back to the buffalo plains again or join raiding parties headed for the Texas frontier. It was a confusing, highly fluid situation. The one certainty was that, in spite of considerable government effort, Comanches remained Comanches. They had not yet been broken of their old habits.

It would be inaccurate to say that the Comanches adapted well, or that Quanah was a model that the tribe as a whole was prepared or equipped to follow. The first generations of Comanches in captivity never really understood the concept of wealth, of private property. The central truth of their lives was the past, the dimming memory of the wild, ecstatic freedom of the plains, of the days when Comanche warriors in black buffalo headdresses rode unchallenged from Kansas to northern Mexico, of a world without property or boundaries. What Quanah had that the rest of his tribe in the later years did not was that most American of human traits: boundless optimism. Quanah never looked back, an astonishing feat of will for someone who had lived in such untrammeled freedom on the open plains, and who had endured such a shattering transformation.

Just finished this too ;) Epic